IntroductionGlossaryThe De-SegThe OperativeThe SecurityThe Untouchables in the Prison HierarchyThe Smell

Rebellions Against the Divine Hierarchy

- The Divine Retribution

- A Riot in the Prison Quarantine

- Mowgli

- The Spaced-Out

- The Wizard

- Life is Beautiful

- An Open Letter

- The Last Resort

- The Release

- Afterword

I wrote this short essay after about three months of staying in a solitary cell of SHU in the Shklov colony. The foundation for it became widely-known in the past book ‘Legends and Myths of Ancient Greece’ by Nikolay Kun, which expounds a number of myths from Ancient Greece, though in a rather truncated and sometimes censored way.

Staying in solitary leads to all the energy of a person being directed inwards, as a general rule, at the thinking process. Not being able to discuss their thoughts with anyone, an inmate pours them out on paper. This was my experience, too: considering the lack of intellectual communication or a possibility to share my ideas, I formulated them in some articles or notes killing two birds with one stone: I didn’t let my brain decay and vented the longing for activity.

Of course, this essay is not an in-depth research, it’s just a short analytical sketch, a reflection on what I read. And even though the theme of prison is not directly addressed in it, I decided to include it in this storybook. Some of the thoughts expressed here may be of interest to some readers. And let professional historians forgive me for my somewhat liberal use of mythological material.

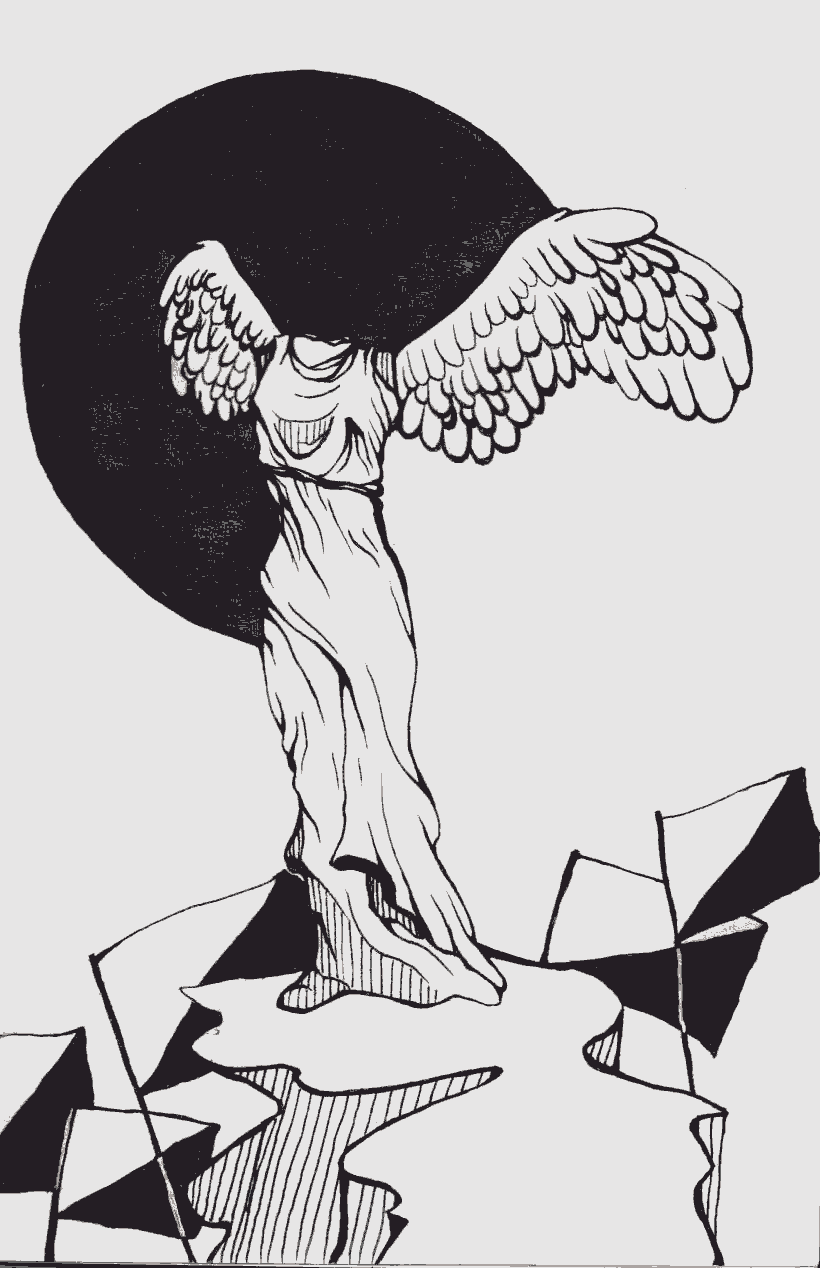

REBELLIONS AGAINST THE DIVINE HIERARCHY IN ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY

INTRODUCTION

Ancient Greek mythology, being a religion at the same time, undoubtedly exercised ideological functions, too — the same as religion does in any class society: justifying social inequality, sustaining the existing state order, reinforcing hierarchy in the minds of people.

A lot has been said and written about how Greek Olympus mirrors society with its system of class domination. Similar to worldly governors, gods of the Olympus demand unquestionable recognition of their superiority, as well as deference and material sacrifice from the people. In the case of disobedience, the person will face dreadful scourge. On the Olympus itself, there is no equality either. There are principal gods and subordinate ones. On the top of the pyramid resides Zeus.

But, like in the real world, in Greek mythology, there is always a black sheep, a ‘disruptive element’ who is able to destroy the eternal order. In our case, it’s either the one who declares that they are equal to gods and aren’t afraid of them because of self-righteousness and vanity, or the one who demands social equality because of their craving for justice. Both of these things make a horrible blasphemy by contemporary standards. Any rebellion, be it the uprising of the masses defending their rights, or a separate undertaking of a lowborn power maniac with inadequate demands beneath them is to be suppressed, and the insurgent should be punished. However, the sheer fact of a presence of such a narrative in Greek mythology attests to an ineradicable, centuries-long craving for casting off the lack of freedom and yoke of oppression, as well as whatever divine halo this yoke is crowned with.

Thus, in Greek mythology, we can easily find events or characters that reject the supreme authority of gods and their demigod relatives that usually made worldly governors. Let’s consider the most distinctive myths around this issue.

THE SONS OF ALOEUS

Otus and Ethialtes were the sons of Aloeus who, in his turn, was born by Poseidon and Canace. The two sons were conceited and were not willing to conform to anyone. From childhood, they were brave and strong and were noted for their unusual height. They started their confrontation with gods with chaining Ares, the god of war and putting him in the dungeon. Ares languished in the dungeon for thirty long months until he was released by Hermes.

Growing bold, Otus and Ethialtes began to threaten other gods:

‘Just let us gain strength and we will pile one upon the other the Olympus, Pelion, and Ossa, rise up to you and abduct Hera and Artemis!”

The response to these earnest threats were the arrows of Apollo that struck the rebels. It should be pointed out specifically that the sons of Aloeus belonged to the mortals.

Otus and Ethialtes died relatively fast and as we will see further, compared to other disobedients, they were blessed.

ARACHNE

Arachne was a Lydian weaver whose works were famous all around. Once in the thick of vanity, she declared:

‘Let the Pallas Athena herself come and contend with me! She will not be able to defeat me’.

Athena came to Arachne under the guise of a crooked old wife, but before punishing the weaver she decided to stay with disciplinary measures, namely, she advised Arachne to contend only with mortals and begged Athena faster to forgive her arrogant words. Arachne didn’t take the old wife’s advice, she rudely interrupted her and only complained:

‘Why doesn’t Athena come?”

Then the goddess assumed her real appearance. Nymphs and Lydian women immediately bowed before Athena and praised her. But Arachne acted differently — she ignored the goddess without rendering her any honours and just insisted on the immediate start of the contest. Consider that there were no judges on it, they were not elected or appointed, though what could have been done without them in this situation.

Athena wove a canvas, portraying her and Poseidon’s argu- ment over the ascendancy over Attica. In the corners of the canvas she depicted gods punishing people for defiance (what a hint!). Arachne, in her turn, wove on the canvas the scenes of gods’ life where gods were actually presented as possessed with human passions (and let’s note, that gods really were like that) and didn’t show any proper respect to them. It’s reported that Arachne’s work was highly competitive with Athena’s work in perfection. So what should the goddess do? To admit her defeat? Naturally, it was unthinkable. The decision of Athena was as simple as top-down governance. She hit Arachne with a shuttle and tore apart the weaver’s canvas. Unable to endure the shame, Arachne wove a rope, made a noose and hung herself. However, vindictive Athena found that even such an outcome was not enough. She took Arachne out of the noose, animated her and turned into a spider, thus devoting her to eternal weaving.

The whole myth is just a quintessence of the blatant injustice based on ‘natural’ inequality. Think about it: Arachne, by honestly challenging Athena, believed there should be unified ‘rules of the game’ for gods and people, and that she, the mortal, could accrue victory if she objectively prevails. Such a view of life assumes a bigger trust to the counterpart, an honest game since, as we remember, there were no judges at the contest. Thus, the act of Athena looks false-hearted and traitorous which didn’t actually embarrass her in the slightest. The goddess lucidly showed Arachne and everyone else that she was not Rousseau or Voltaire and the principle of equality before the law was unfamiliar to her. But she generally accepted the sword law. Since using violence in the situation when her competitiveness didn’t lose, to say the least, Athena accentuated the inherent, incontestable inequality of gods and mortals. This myth and its contents seem to assert: ‘Let you be as wise as Solomon, let the right be on your side, gods will anyway tread you to pieces just because they are gods’.

PROMETHEUS

Prometheus is a titan, the son of goddess Themis. He used to be Zeus’s ally in the battle for power on Olympus but fell

into the cloud-assembler’s disgrace for adherence to the ideals of humanism. Living on the Olympus in the atmosphere of constant celebration, with no want for anything, he took pity on the mortals. Seeing the suffering to which they were condemned by gods, he stole fire from his friend Hephaestus’s smithy (the son of Zeus, by the way) and delivered it to the people. Moreover, after coming down to earth, Prometheus continued to provide aid to the mortals: he domesticated a wild bull, harnessed a horse to a cart, taught people how to craft, read, count, write and build ships, disclosed to them the force of herbs.

Let’s note that Prometheus didn’t just give people a one- time instrument that could make their lives easier, but helped them to harness the forces of nature that at that time were directly identified with the force of gods. By this, Prometheus made them much more independent. Was it in Zeus’s cards? Hardly so. His servants brought Prometheus to the cliff, and his friend Hephaestus was instructed to chain him to the rock and empale Prometheus’s chest fastening him to the rock with a spike. Suffering from remorse but unable to go against his father’s will, Hephaestus carries all this through.

But there is another aspect that is bothering Zeus and multiplying his anger and suspicion towards Prometheus. Prometheus knows the mystery: how and when Zeus is to be overthrown from the Olympus and lose his power. Zeus, naturally, intends to extort this secret from Prometheus.

One by one Prometheus is visited by various deities — Oceanus, the Oceanids, Hermes — who try in every way to persuade him to submit and share the mystery with Zeus. But Prometheus remains adamant. With Hermes he is specifically straightforward: ‘I will not give up my grief for the slavish serving to Zeus. I'd better be chained to this rock than become a faithful servant of the despot Zeus. There is no execution, no tortures that he could use to frighten me and get a single word from my mouth!”

Well, if that isn’t revolutionary, what is?

For this defiance, Zeus throws the cliff where Prometheus is tied to down to the eternal darkness, where he then spends centuries. Having raised him again, Zeus prepares a new chal- lenge for Prometheus’s revolutionary morale. Every day an eagle flies to the cliff and leaves only after pecking out his liver.

His liver grows back overnight, and the torture repeats in the morning. Meanwhile, the titans overthrown by Zeus during the fight for power have been forgiven and are brought back from the Tartarus to the surface as those who had acknowledged the authority of the cloud-assembler. In contrast, Prometheus stays adamant and proudly endures his suffering (it should be pointed out that the fate of ardent enemies of Zeus turned out to be more desirable than the lot of the out-of-favour ally...). His mother Themis and the hero Heracles come to him and all ask for one thing: to accept the electoral results... ugh, I mean, to acknowledge Zeus a supreme governor and reveal the Secret to him. Heracles treated Prometheus in a chivalrous manner: he killed the eagle who had been tormenting him for so long. Hermes flew from the Olympus immediately and yet again promised freedom to Prometheus in exchange for the Secret. And here something broke down inside the rebel. Prometheus told Zeus how to avoid the overthrow: the Olympian alpha male just needed to stay away from the sea goddess Thetis since any son that is born to her will be more powerful that his father. Thus Prometheus gained liberty in return of pursuance of Zeus’s will.

The myth of Prometheus is noteworthy specifically for the motivation that inspired the hero to commit a crime against the divine order of governance. This is not the lust or rapture of valour of Otus and Ethialtes, nor the self-admiration caused by the extraordinary artistic skills of Arachne. In the case of Prometheus, the motivation is the living compassion, love to people, the feeling of justice and the rejection of slavery. And it doesn’t matter that Prometheus has broken after long centuries, no longer able to endure the torture. I would double- down on the fact that being an immortal titan, he possessed everything. He was treated with affection by the governor and well-received on the highest levels of power. However, he sacrificed all this to ease the suffering of people in this world. I say it straight: Prometheus is the first known humanist.

THERSITES

The peak of the egalitarian episodes of Greek mythology, in my opinion, is the episode from Trojan cycles with a warrior named Thersites in the lead role. This is not about an individual rebellion anymore, but about an attempt to raise a popular revolt. But first things first.

Let me remind you of the plot of the Trojan cycle: Paris, the son of King of Troy, visits a palace of the local king Menalaus in Laconia and is being received as an honourable guest. However, he insidiously takes away his wife from the palace, the beautiful Helen (a natural daughter of Zeus, by the way). Menelaus can’t tolerate such humiliation and after consulting his brother Agamemnon, he decides to declare war to Troy to retaliate on Paris and get his wife back. He was able to engage in this campaign as headliners with almost the whole pantheon of contemporary heroes: the Ajax brothers, Odysseus, Achilles and many others. All of them came from the supreme aristocracy. They were sons or grandsons of kings, gods, and demigods — let’s pay attention to this fact, it is extremely important. Apart from them, the campaign was supported by 100 thousand warriors, obviously, not aristocrats, but freemen and landlords. The siege of Troy lasted for 10 years. On the 10th year, the event in question actually happened.

Agamemnon decided to yet again attack Trojans by the walls of the town. However, before that, he wished to test his troops for loyalty. He called a popular assembly of all the warriors he had and addressed them. He spoke about the hardships of war, the idleness of the siege and about the fact that the gods probably desire that the Greeks win. The reaction of warriors was immediate — like an insurgent sea, they dashed to the ships, glad of the opportunity to go back home. That figures: a simple man from Hellenic province hardly ever craved fighting and dying for the concerns of the heart of the local king.

And here, a well-known to us, Pallas Athena took the stage. An important point should be made: the myth of Troy is not a fairy-tale, not a fancy of the author, but rather a confabulated story because it is based on a true story despite the existence of fairy-tale characters. So we will look at what happened later in the chronicle of historical events.

So, having appeared before Odysseus, Pallas Athena told him to bring the warriors back as soon as possible. Odysseus didn’t need to be asked twice. The king of Ithaca snatched away the scepter (the sign of supreme power) from Agamemnon and began to actively urge the warriors to come back to the assembly, so actively that the scepter went in a whirl over the backs and heads of the fugitives.

The author dissembles the fact as to whether there were victims of this ‘urging’, but I assume that without killing one of the several warriors Odysseus could hardly stop such a mass of people. He was successful in it — the warriors returned to the assembly and calmed down, just Thersites alone didn’t settle down and started to shout. Thersites, the author informs, always bravely spoke out against kings (to be fair, Thersites himself was related to Diomedes, the king of Argos). This time he pushed back against Agamemnon saying that he had already captured a lot of trophies and bond-maids, and it’s time for him to be seated and for them, simple warriors, to go back home. Let Agamemnon fight against Troy alone! And now let’s remember that most kings were related to gods and we’ll realise how far Thersites went, against whom he raised his voice.

Generally, everything in the speech of Thersites was logical and fair, but from then on really strange things began. Odysseus comes to Thersites and says:

‘Don’t you dare, you fool, defame kings, don’t you dare to speak about returning to your home town! If I ever hear again you, lunatic, defame king Agamemnon, let my head be cut off from my square shoulders, let them stop calling me the father of Telemachus, if I don’t grab you, tear your clothes apart, beat you up and banish you from the popular assembly to the ships, and you will be crying in pain’.

In support of his words, Odysseus hit Thersites with a scepter on the back so that the latter’s eyes flowed with tears. Then, according to the author, everyone laughed loudly and said looking at Thersites:

‘Odysseus has carried out a lot of gests in the committee and in battle, but this is the best of his exploits. How he restrained the wrangler! Now he will not dare to defame the kings favoured by Zeus anymore’.

Here, I believe, the author sins against the truth a lot, exposing all Greek warriors as hopeless idiots who don’t have their own opinion. Consider this: only a few minutes ago the warriors were dashing to their ships forgetting about the ‘kings favoured by Zeus’, and just brutal force and the authority of Odysseus could get them back. And now thousands of warriors, who had just wished for doing what Thersites suggested, start to laugh at him though he expressed the aspirations of every and each of them. Let’s not forget that often historical events in chronicles and myths are reshaped in order to please the ruling class, and in our case, to please the kings-noblemen and their relatives who would naturally be interested in demonising Thersites by exposing him as a freak, a wrangler who is beaten up just for fun. It’s more likely that Odysseus’s act was cheered and loudly praised by people like him: kings, the blue blood of the Greek army and maybe his confidants from common soldiers. Simple warriors, I believe, were looking at the scene with sadness, but they didn’t dare to openly support Thersites. Over nine years of the siege they got used to obeying to their leaders, moreover, they understood perfectly well that if there is a rebellion, Odysseus will be immediately supported by the top militaries. This is why common soldiers were looking at the humiliation of Thersites clenching their teeth with anger and fear, and not jovially laughing. This version is much more probable, in my opinion. But the story of Thersites doesn’t end there.

From the far-away Pontus, the Amazons came to help out the Trojans. The battle was boiling yet again, where women were fighting under the leadership of queen Penthesilea. In the heat of battle, she was killed by Achilles. Looking at Penthesilea, Achilles understands that he loves her and bows his head over the dead in sorrow. Here it would be great if Penthesilea opened her eyes full of passion and Achilles revealed a chest protection under her cyclas and kissed his lover amid the thickening combat. Sadly, Thersites brings rain on the parade again. Coming up to Achilles, he began to berate him (though it is not clear from the text what for), and then probably decided to pique him in an extremely sophisticated way. He took a spear and pierced an eye of the dead Penthesilea. Having recovered from the shock, Achilles hit Thersites in the face so strongly that it killed him on the spot, ingloriously ending the life of this character who was thrown mud at by the author of the Trojan cycles.

Let’s try to get an objective and common sense insight into what happened.

First of all, Achilles belonged to heroes-demigods and was vitally interested in the victory of Greeks over Troy. This victory gave him rich trophies (including slaves) and surely the expansion of his domain, saying nothing of the fame and prestige. Second of all, before Achilles joined the battle (he entered the battle when it was already on), the Amazons were seriously pressing the Greeks; the latter began to retreat and were almost pushed to their ships. They were so close to getting on those boats. And Achilles knew very well where they would have gone if they had boarded them. An extremely unpleasant

situation was created for the leaders... The smallest spark, like the call of Thersites, was enough for the army to wave farewell to their chiefs — like, you fight yourselves, and we are going home. The precedent is fresh in the memory of Achilles. In this situation, the aristocracy decided to stay one step ahead of themselves and in the confusion of the battle Achilles kills such an inconvenient fighter as Thersites since he can use the situation any moment and get his own back for the recent humiliation. However, an open murder of an equal to himself was formally inexcusable even for Achilles (later he even had to sail to Lesbos to clear himself from the abomination of the spilled blood by bringing sacrifices to Apollo and Artemis). The author of the myth-chronicle vitally needed to make a proper excuse to the murder, the same as Achilles himself would probably make among the aristocracy: lunatic Thersites was allegedly scoffing at the dead body... While in reality Achilles just seized (maybe even by prior arrangement with other aristocrats) the occasion that was ideally suited for the elimination of the dangerous rebel. I will not assert that this narrative is the only truth, but I think it’s a viable option.

CONCLUSION

All heroes-rebels from the Greek myths, mortals, and non- mortals, have one thing in common: the all came to a sad end, in layman’s terms. They were either forced to be in favour of gods’ will and just because of this, they were forgiven or were ruthlessly eliminated. None of them won this stand-off. And this is rather consistent, and could not have been otherwise — in a Greek myth (and, perhaps, in the conscience of ancient Greeks)

there wouldn’t be a place for such a character, he would fall out of the frame of reference. Arachne wins in the contest with Athena, and the latter leaves the ‘battlefield’ with her head low. Otus and Ethialtes are entertained by Zeus’s wife... Naturally, this is inconceivable for a Greek myth. This implies the most important function of the Greek religion — the educational- ideological role it plays. Myths were meant to demonstrate in an instructive way: an argument with gods and their satraps on earth (kings, aristocracy) is useless, fatal for the wrangler, and the only result of it will be the flawless victory of a higher person in the hierarchy. Thus, through subordination to divine masters, people were put into the habit of subordinating to worldly masters.

But looking behind the cover of edification and preaching we will see the most important thing — what motivated Odysseus who was beating Thersites, Zeus who was tormenting Prometheus, Athena who forced Arachne to commit suicide. We will see fear. Fear of gods, seemingly powerful and invincible before a vast disempowered mass of the mortals, in the midst of which, Bravehearts are born over and over again and openly challenge the ‘eternal’ order. And it becomes clear: the mythology only reflects the actual perpetual horror of the rulers in the face of the slightest possibility of a popular uprising.

Yet, however, the Greek people were being scared by the educational myths, they have inevitably made way to new Thersites and Prometheuses. And I want to believe that at some point they will overturn the Olympus.

October-November 2012

He who conceits himself the master of heaven,

Will be cast down to hell by his own children.

Poseidon and Zeus treated like this

Kronos who owned everything on earth.

With no fear before Athena stood

Arachne and called her out to a contest.

A yester gladiator fought consuls

A hundred years before the Crucifixion of Christ.

Not everyone dares to challenge the authority,

To loudly declare that the cold idol is dead,

And though he never saw equality in life,

To put an equals sign between the cloud-assembler and a slave.

Though even now the hiss of lashes doesn’t cease,

The heroes of the past, you are not forgotten!

New Thersites proclaim on the Internet

And a new Prometheus pours petrol into bottles…

March 2015

IntroductionGlossaryThe De-SegThe OperativeThe SecurityThe Untouchables in the Prison HierarchyThe SmellRebellions Against the Divine Hierarchy